Gargantuan sunspot 15-Earths wide erupts with another colossal X-class solar flare (video)

United States

Breaking News:

Washington DC

Monday, May 20, 2024

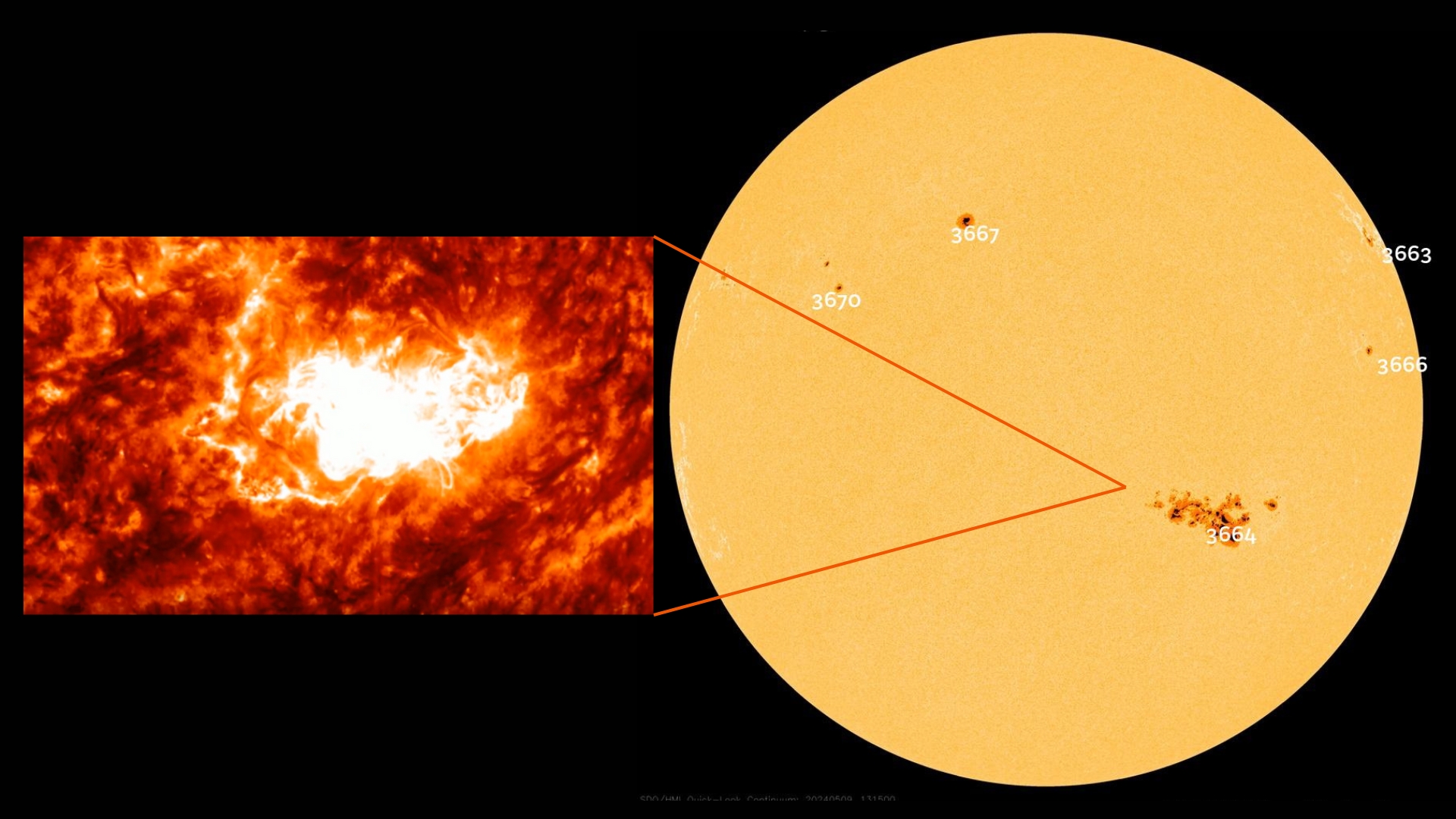

AR3664 is no ordinary sunspot.

The behemoth dark patch on the sun’s surface has ballooned in recent days, becoming one of the largest and most active sunspots seen this solar cycle.

AR3664 garnered the attention of scientists earlier this week as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center issued a warning of increased solar flare risk from the solar giant on Tuesday (May 7).

“Region 3664 has grown considerably and has become much more magnetically complex,” NOAA’s SWPC reports. “This has led to increased solar flare probabilities over the next several days.”

The giant sunspot has more than lived up to expectations. Firing out countless powerful solar flares in recent days, including a colossal X-class solar flare this morning (May 9), peaking at 5:13 a.m. EDT (0913 GMT).

Related: Sun explodes in a flurry of powerful solar flares from hyperactive sunspots (video)

Solar flares are eruptions from the sun’s surface that emit intense bursts of electromagnetic radiation. They are categorized by size into lettered groups, with X-class being the most powerful. Then there are M-class flares that are 10 times less powerful than X-class flares, followed by C-class flares which are 10 times weaker than M-class flares, B-class are 10 times weaker than C-class flares and finally, A-class flares, which are 10 times weaker than B-class flares and have no noticeable consequences on Earth. Within each class, numbers from 1-10 (and beyond for X-class flares) describe a flare’s relative strength.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The X-flare this morning clocked in at X 2.25 according to spaceweatherlive.com, measured by NASA’s GOES-16 satellite.

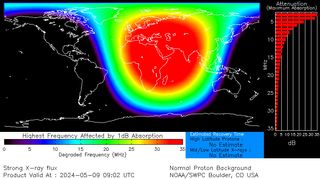

Powerful solar flares like the one observed this morning can cause shortwave radio blackouts on the sunlit side of Earth at the time of the eruption. As such, the X-flare this morning caused shortwave radio blackouts across Europe and Africa as seen in the image above.

The radio blackouts are due to the strong pulse of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation emitted during the eruption.

Related stories:

The radiation travels toward Earth at the speed of light and ionizes (gives electrical charge to) the top of Earth’s atmosphere. (Note: these ionizing X-rays are not to be confused with coronal mass ejections (CMEs) by which plasma and magnetic fields erupt from the sun, traveling at slower speeds, often taking several days to reach Earth).

This ionization causes a higher-density environment for the high-frequency shortwave radio signals to navigate through in order to support communication over long distances. The radio waves that interact with electrons in the ionized layers lose energy due to more frequent collisions, and this can lead to radio signals becoming degraded or completely absorbed according to NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center.

Sprawling out at almost 124,000 (200,000 kilometers) from end to end, the sunspot AR3664 is currently 15 times wider than our home planet, according to Spaceweather.com.

It is so big that it can be seen from Earth without the need for magnification. If you still have a pair of solar eclipse glasses lying around after April 8’s total solar eclipse, you can use them to safely observe the sun and see the mammoth sunspot cross the solar disk.

But remember NEVER look at the sun without appropriate solar protection. You can find out how to safely observe the sun with our helpful solar observation guide.

The vast size of Sunspot AR3664 rivals Carrington’s sunspot of 1859, as depicted in this image from Spaceweather.com. Carrington’s sunspot is known for its explosive rampage between August and September 1859, during which it fired off a series of powerful solar flares and CMEs, resulting in major geomagnetic storms that ignited telegraph offices and triggered auroras as close to the equator as Cuba and Hawaii.

Read more: The Carrington Event: History’s greatest solar storm

Although studies suggest Carrington-class solar storms occur every 40 to 60 years or so (and we are long overdue), there is no evidence that any CMEs currently en route from previous solar eruptions this week could cause a new Carrington Event, according to Spaceweather.com.

Scientists are keeping a close eye on this ever-growing sunspot while it continues to face Earth.