She Was No ‘Mammy’

United States

Breaking News:

Washington DC

Sunday, May 19, 2024

I

am the granddaughter of domestic workers. My maternal grandmother was Luretha Little, an only child, who left her parents behind in North Carolina, and then her husband and two young sons in Virginia in search of freedom in New Jersey, where her sons eventually joined her and where my mother was born in 1955. In Newark, Luretha and her second husband, Elijah Griffin, had four more children. They ran a janitorial business, cleaning the offices of white doctors in Woodbridge and white scientists in New Brunswick. Sometimes they brought their children and put them to work: the twin boys swept the floors, and my mother dusted desks and polished ashtrays. My paternal grandmother, Hilda Ramdoo, was nicknamed Dolly because she was a pretty baby. One of nine children born in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, she had seven of her own. By the time my father was an adult, his mother had temporarily left her husband, Antonio Tillet, and remaining six children to work in Caracas, where she cleaned the homes of the Venezuelan elite; she later went to Boston, where her entire family eventually joined her, and where I was born in 1975.

I think a lot about these two women and their countless hours of labor in the homes or offices of others. Though they were separated by race, nationality, and age, because of their gender and class they were relegated to the same job. But they also had full lives. Seven children each. Luretha loved Mahalia and Motown. Dolly was one of the first women to start a Carnival band in Trinidad. They were pious and proper and quick-tongued and outspoken. I think a lot about what existed for them beyond work when I look at Gordon Parks’s most memorable image: the 1942 photograph he initially labeled Washington D.C. Government Charwoman, but renamed American Gothic during the revolutionary 1960s.

More than half a century later, Parks recounted making this first portrait of Ella Watson, the 59-year-old African American cleaning woman who, like him, worked at the Farm Security Administration offices in Washington, D.C. “So it happened that, in one of the government’s most sacred strongholds,” he wrote, “I set up my camera for my first professional photograph.”

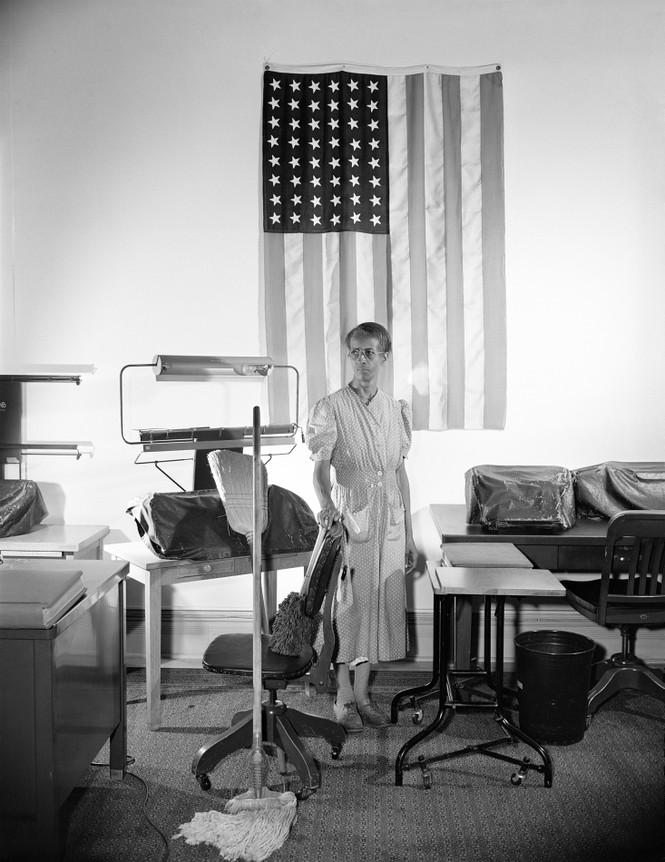

“On the wall,” he continued, “was a huge American flag hanging from the ceiling to the floor.” Parks asked Watson “to stand before it, placed the mop in one hand, a broom in the other, then instructed her to look into the lens.”

This capture of Watson at work—wearing a neatly pressed polka-dotted puffed-sleeve dress and wire-rimmed glasses, her hair parted to the side, with a straw broom and rag mop on either side of her and a slightly out-of-focus American flag hanging behind her—is now so familiar to me that I don’t remember when I first saw it. But I didn’t know until recently that it is what Parks considered his “first” professional photograph, setting him on the path to becoming one of the most innovative and influential photographers of all time.

In July and August 1942, Parks took more than 90 photographs of Watson, her family, and her community, in a project that rejected long-standing caricatures of Black women as mammies or subservient maids. More than a decade before hundreds of Black women domestic workers helped organize the Montgomery bus boycott, Parks’s series with Watson revealed Black domestics as they often were: patriotic, political, and pious.

In his memoir, A Choice of Weapons, Parks recalled entering the FSA offices for the first time, walking “confidently down the corridor, following the arrows to my destination, sensing history all around me, feeling knowledge behind every door I passed.” Roy Stryker, the head of the FSA’s Historical Section, sensing that Parks’s naivete would not serve him or his future subjects well, encouraged him to leave his camera behind and get to know the city by going for a bus ride, taking in a movie, shopping at a drugstore or a department store, or dining at local restaurants. “I wanted to kill everyone,” Parks said about those experiences. “I’ve never been so mad.” Unlike in Saint Paul, where he came of age, or even his more recent home, Chicago, in D.C., he faced the harsh reality of the district’s strict segregation laws and was denied service or entry everywhere he went. Furious, Parks told Stryker that he needed to document this story of American racism and then plotted his plan in bold strokes. “I wanted to photograph every rotten discrimination in the city, and show the world how evil Washington was,” Parks said. “I had the biggest, vaguest ideas in the world.” After making it clear that such a project would require him to hire all of Life magazine’s photographers for the rest of their lives, Stryker encouraged Parks to focus on and follow one person to achieve his goals. Stryker indicated a woman who was mopping the hallway floor nearby. “Go have a talk with her before you go home this evening,” he said. “See what she has to say about life and things. You might find her interesting.”

Born in late March 1883 in Washington, D.C., Ella Watson had been a domestic for most of her life by the time she met Parks. In 1898, at age 15, she left school and later that year found a job ironing at the Frazee Laundry in Washington. She worked intermittently, listing “maid” and “laundress” as her employment on the census until she found a temporary position as a custodian at the State Department in 1919. The following year, she doubled up, working as a caretaker in a white family’s home and cleaning another federal agency building. She managed to secure steady employment at the Post Office Department for most of the 1920s, then moved to the Treasury Department (where the FSA was also located) in 1929; she remained there until 1944. “I came to find out a very significant thing,” Parks later remembered. Watson “had moved into the [office] building at the same time, she said, as the [white] woman who was now a notary public. They came there with the same education, the same mental facilities and equipment, and she was now scrubbing this woman’s room every evening.”

I have always wondered whether Parks saw parts of his biography in Watson’s story. Long before he worked for the railroad, much less became a professional photographer, a teenage Gordon Parks was homeless in his new city of Saint Paul. He worked weekends at his boardinghouse to make ends meet, washing dishes and mopping floors. A few years later, like millions of Americans during the Depression, he was destitute again. Having lost all his belongings on an earlier trip to Chicago, a desperate Parks got a gig at the Hotel Southland. Because of his race, this run-down establishment barred him from renting one of the rooms he was responsible for cleaning.

Having to clean for the hotel’s white, working-class, and almost always drunk guests brought out the worst in him. The Southland was filled with a “bad breath of smoke, alcohol, sour bodies and human excrement” and “pickpockets, alcoholics, bums, addicts, perverts, panhandlers,” and the only way Parks could survive was to “hold my own here, where profanity meant prestige and politeness invited abuse.” Hating every day of his short-lived experience there, Parks concluded, “It was a harsh and ugly time,” marked mainly by his “longing for the time when I could get into a tub of hot water and soak out the smell of the place.”

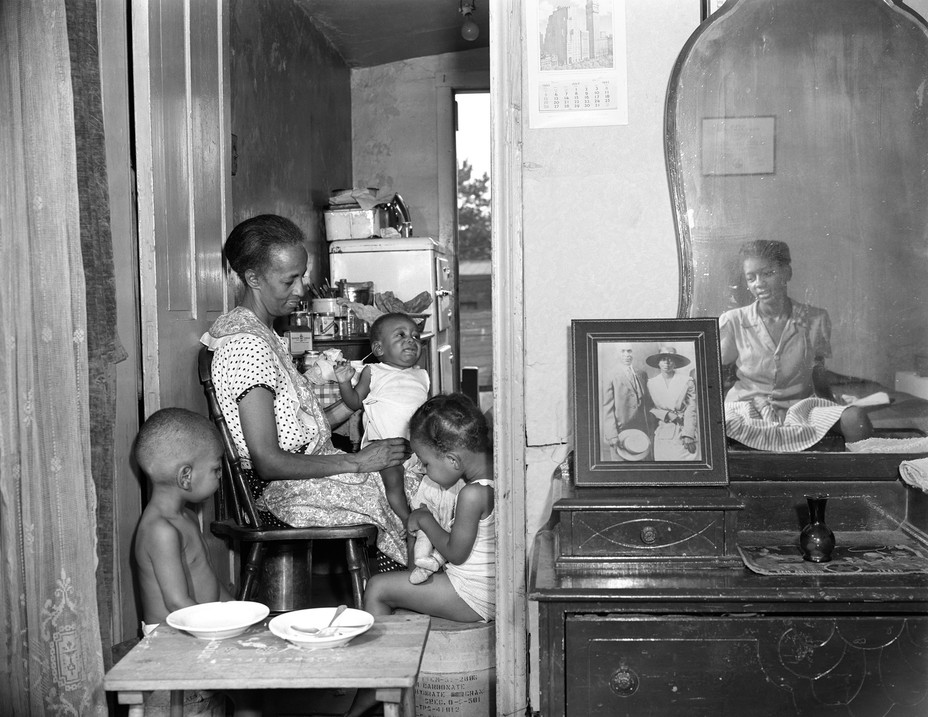

I do not know if Parks divulged his past to Watson, but she shared much with him. “Would you allow me to photograph you?” he awkwardly asked her one early-summer evening in 1942. “In an old dress like this?” she humbly replied. Soon Parks had his most enduring photograph, but he realized he knew little of his subject beyond the image. When he approached her later to ask if he could continue to document her and learn more about her life, Watson joked that it might take some time because she was a grandmother. She then told a life story that sounded to Parks like “a bad dream.” By the time he met her, her husband had died (in 1927), and she was raising her adopted teenage daughter and her adopted daughter’s nieces and nephews. Watson, a single mother and the sole provider for the family, was left to survive on an annual wage of $1,080. And she knew she was locked permanently into this status.

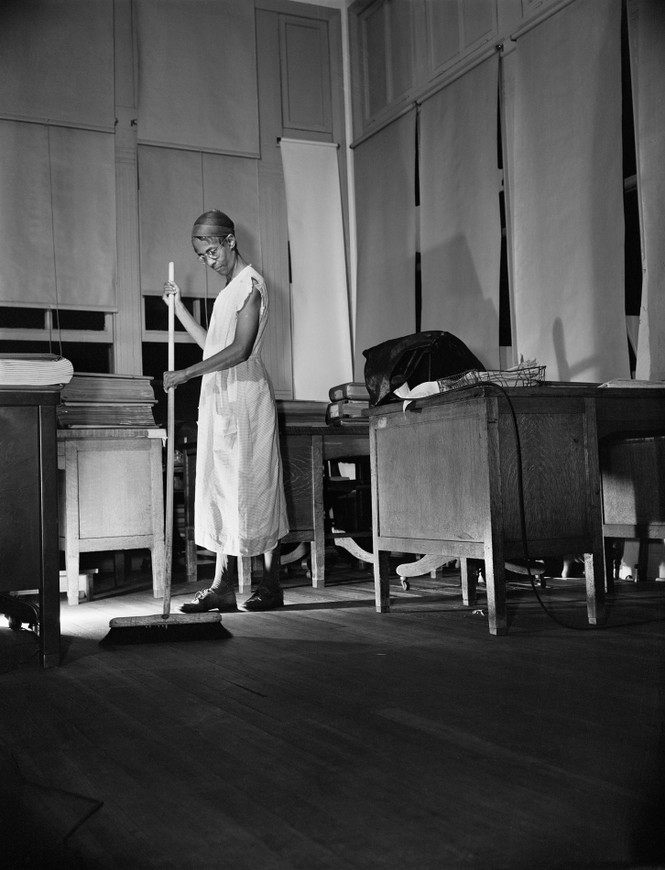

Whether Parks consciously identified with Watson as a domestic remains unclear. But in the actual photographs, we can see his identification with and respect for her as a laborer in unexpected ways. Rather than remove all evidence of himself in the portraits of Watson cleaning the offices, he subtly included traces of his photography equipment. Parks established a reciprocity between their lives and their labor. He knew it was not a one-to-one correlation. “By comparison,” he reflected after learning of Watson’s hardships, “my experiences were akin to a peaceful afternoon.” The images were trenchant critiques of the limited economic opportunities available to Black people, particularly Black women in Jim Crow America, while they also told Watson’s story with visual nuance and depth.

Stryker immediately understood the disruptive power of Government Charwoman. Balking after Parks showed it to him, he said, “Well, you’re catching on, but that picture could get us all fired.” Aware that southern members of Congress had already complained about the FSA’s publishing images of Black people impoverished in the segregated South, Stryker encouraged Parks to continue documenting Watson.

The most dominant image of Black domestic workers in mainstream America at the time was that of a mammy, a Black woman who happily served at the whims of white employers. By 1941, the image had peaked: Hattie McDaniel won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her role as Ruth “Mammy,” a formerly enslaved woman on the Tara plantation and house servant to Scarlett O’Hara in the pro-Confederate movie Gone With the Wind. Years later, when a friend criticized her for “playing so many servant parts, or ‘handkerchief heads’ as they came to be called,” McDaniel responded, “Hell, I’d rather play a maid than be one.”

Although Parks was not alone in creating a counternarrative to racist stereotypes, his image remains one of the most enduring. Two years before Parks arrived in the capital, his literary hero Richard Wright sent his agent a manuscript titled Slave Market (later renamed Black Hope), about the plight of Black housemaids. Wright hoped the novel might “reveal in a symbolic manner the potentially strategic position, socially and politically, which women occupy in the world today.” But he never published the book, and another eight years would pass before Lutie Johnson, a domestic worker turned blues singer, would appear in print in Ann Petry’s social-realist novel The Street.

Parks never saw Watson as just a symbol. Through sustained documentation of her life, the civil-rights aesthetic he pursued and perfected for the rest of his career took form. In that brief encounter with Watson, her friends, and her family, Parks realized his capacity to depict Black people in his art the way he knew them in the world: as multidimensional, multitudinous, and agents of social change.

He achieved this, in part, through a swap. Parks later admitted to having Grant Wood’s American Gothic in mind when he placed Watson in a pose similar to that of both figures in Wood’s 1930 painting. Parks likely saw the painting—now one of the most recognizable of 20th-century American art—during a train layover in Chicago in 1937. Unlike the sharp social commentary of the FSA photographs, Wood’s painting was both bucolic and nostalgic. The obvious middle-classness harkened back to an age of prosperity and stability before the Great Depression. “What does matter is whether or not these faces are true to American life,” Wood wrote about his models in a 1941 letter, “and reveal something about it.”

Recently, I went to see Wood’s American Gothic on a lark. I had seen the painting many times as one of the many tourists who flock to the American wing of the Art Institute of Chicago, looked at it from various angles, and debated its import as kitsch or haute culture. But this time, I had Parks and Watson in my head, and I found myself less interested in the farmer and his daughter (many people mistake the woman for a wife) and more invested in Parks’s transformation of a double portrait into a single one.

In Parks’s version, Watson stood in for both figures. In Wood’s painting, the division of labor falls along traditional gender lines. The older man and the younger woman are outdoors, and the pitchfork is the main clue to their labor. The farmer uses it daily, making it a crucial part of his routine and work, as the painting suggests, in public. The young woman’s gaze suggests a dependency on him, and her kitchen garb indicates that she does not work alongside him but might take care of the home. By replacing those two figures with Watson, a Black cleaning woman, Parks troubled the notions of gender, race, and work. As Watson cleaned those stairwells and offices in the after-hours, the wartime bureaucracy of the FSA became a domestic space, and women’s labor was no longer unseen.

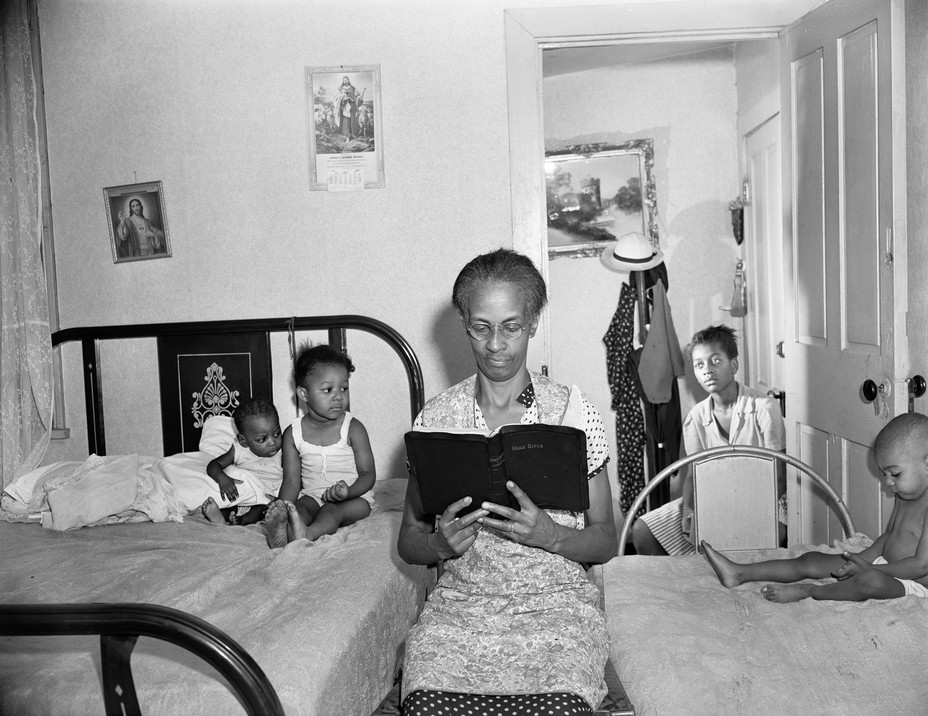

I am drawn to those photographs that fully refuse Watson’s invisibility and revel in her interiority. Parks travels with her far beyond the office building and witnesses her different types of emotional, familial, and intergenerational labor: her preparing to go to and returning from work; her feeding and dressing her grandchildren, and combing their hair.

Interspersed are moments in which Watson created an alternative to the racism she experienced at work and a curative to her daily grind. As poignant as but less popular than her overt dissent in front of the American flag in the most famous photograph is her embrace of religious ritual and her exercising her right to rest. Tenderness is on display when Watson’s grandchild naps midafternoon or when we see her silhouette projected on the mirror behind her bedroom altar. Eyes closed, head down, Watson appears in a solo portrait again, but this time in prayer. Parks helps us see how, despite her economic poverty, surrounded by rows of neatly lined-up statues and candles, Watson made her home a sanctuary, a place where she, and maybe even he, for a time, could connect to something far better than the segregated country into which they both were born.

“I was in my very late teens when I was first made aware of the images,” Ella Watson’s great-granddaughter Rosslyn Samuels told me in an interview. “And I didn’t grasp the magnitude of it until my later years, because, to me, she was just Grandma.” When she saw Parks’s photographs, she said, “I thought, Oh, someone took professional pictures of her. I regret not knowing about them when she was alive, because she and I shared a bedroom, and we talked about everything.” Knowing Watson only as a retiree meant that Samuels’s primary memories of her great-grandmother are more like the photographs Parks took outside the office, the large majority of moments he documented: Watson as a loving, pious, nurturing Black woman who seemed to delight in looking after those she loved.

And here, Watson still inspires. “I get an overwhelming feeling when I look at Parks’s photographs of her now,” Samuels revealed. “It’s just like, ‘Wow.’ But … I’m not surprised, because she was always so big to us. She had that impact on a lot of people. We revered her. And it’s not like she commanded it; she just had a certain effect on people.”

Fortunately, one of them was a 29-year-old photographer named Gordon Parks.

This article has been excerpted from “‘She Was Always So Big to Us’: Ella Watson as Style and Substance,” an essay by Salamishah Tillet that appears in Gordon Parks’s new book, American Gothic: Gordon Parks and Ella Watson.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.