This parting was not sweet sorrow — Part 1

United States

Breaking News:

Washington DC

Friday, May 17, 2024

AUTHOR’S NOTE: A similar version of this story first appeared in the Redoubt Reporter in 2010.

One of the highlights of Rusty Lancashire’s retelling of George Dudley’s 1967 muddy, drunken mess of a funeral involved the moment that one of the attendees fell into the open grave.

In fact, Lancashire, who lived on a Ridgeway-area homestead for more than 50 years, took such delight in the story that she told it repeatedly, and some long-time residents across the central Kenai Peninsula can still remember hearing the tale.

“Rusty’s rendition of it was hysterical,” said a chuckling Peggy Arness, who, along with her husband Jim, once employed Dudley as a longshoreman at their Nikiski dock.

Another person who heard Lancashire tell the story was Soldotna’s Al Hershberger, who first met Dudley in about 1950 and recalled much of the man’s early history. “Ah yes, George Dudley, an unforgettable character,” said Hershberger. “Dudley was an easy-going, laid-back sort of guy, always laughing and joking, as well as hard drinking.”

Although Arness and Hershberger knew Dudley, neither of them attended his funeral. In fact, by 2010, there was probably only one person still living who was an actual eye-witness to the ceremony: Hedley “Hank” Parsons, who was a laborer on the central peninsula for more than 30 years before moving back to his home state of New Hampshire in 1984.

<!–

–>

“I was working for Morrison-Knudsen at the time on the White Alice project,” Parsons recalled in 2010. “We’d take a trip or two into Kenai about every day for something, and I guess the funeral was kind of news, and so I swung in and visited.”

Parsons’ remembrance of that May 5 event matched in most respects the story told by Lancashire. It also closely matched the contents of an unsigned letter — discovered in 2010 — that described the funeral in colorful detail. The letter was found in a cardboard box of unrelated materials that had been donated to the Anthropology Lab at Kenai Peninsula College’s River Campus.

Addressed “Dear Hugh,” the letter began with a lament for “the passing of Kenai from the scene as a community completely unique.” It then offered up the Dudley funeral as proof that the “old special flavor of Kenai,” while diminished, had not altogether vanished.

Because the letter referred to Hugh having “dealings with George over right of way,” several longtime residents concluded that the recipient of the letter must have been Hugh Malone, who was a surveyor at the time and later went on to serve on the Kenai City Council and in the State Legislature.

The identity of the letter writer, however, remains murky, although almost certainly it was a man. At one point, the writer appears to identify his occupation: “I don’t like funerals. I think they are barbaric and years ago swore that the next funeral I attended would be my own, and if I could manage, I’d skip that one, too, but somehow, after a few drinks, and swapping lies with a couple of other divers at Larry’s (Club), it seemed the thing to do.”

<!–

–>

Divers were being employed at the time during the construction and erection of oil-drilling platforms in Cook Inlet, and several long-time area residents were unable to recall a single female diver working at that time.

And despite the writer’s reluctance to attend funerals, he seemed delighted that he had made the effort to go to Dudley’s: “It was a funeral to end all funerals, and it and the wake that followed could happen only in Kenai, believe me.”

Dudley’s Backstory

On the morning of the funeral — a Friday — a death notice appeared in The Cheechako News on page 13, featuring this headline: “North Kenai Man Found Dead in His Home.” The four-paragraph article identified 58-year-old George Coe Dudley as the deceased, and said that he had been found on Sunday by longtime friend Robert Murray, who had been staying with Dudley for a number of years.

The article set the time of Dudley’s passing as 4 a.m. and attributed the death to “natural causes.”

Dudley was a commercial salmon fisherman who had been born in California in February 1909, been an architect/builder in Los Angeles County in the mid-1930s, been married twice, worked for the Alaska Railroad, and once operated a hotel in Anchorage. He had spent the last three decades of his life in Alaska.

However, neither this small collection of facts nor the simple wooden cross bearing a small brass name plate in the Kenai Cemetery adequately describes the man George Coe Dudley was and explains why his funeral became such a wild affair.

To understand these things, one must peer further back in time.

A 20-something George Dudley made his way to Anchorage in the late 1930s. For much of the next decade or so, he experienced some great successes but also some toppling failures. For instance, Al Hershberger remembered Dudley telling him that at one time the renowned Alaska painter Sydney Laurence gave him one of his paintings — worth a staggering sum today. But the artwork was one of the many symbols of his financial good fortune that eventually disappeared.

“Dudley was a con artist when it came to getting a drink, as most alcoholics are,” Hershberger said, “but he was not a person given to making up stories about things he had done.”

Although the timeline of Dudley’s life events is not well known, certain moments stand out. He and colleague L.E. Lind built and helped operate the Lind-Dudley Hotel in the Spenard area, and his second marriage, in 1940, was to Jane Burke McKnight, the once-divorced daughter of George Barnes Grigsby, a prominent Anchorage attorney and president of the Anchorage Bar Association.

<!–

–>

“How he ever met Grigsby — how he ever got in with that family — I really don’t know,” said Hedley Parsons. “He might’ve been from kind of halfway civilized family before he came to Alaska.”

After the marriage ended in divorce, according to Hershberger, “the ex-wife was blamed (by Dudley) for the demise of his fortunes. This may or may not have been the case.”

Neither of Dudley’s marriages lasted long. The Dudley-McKnight nuptials occurred before a U.S. Commissioner, but Dudley’s first marriage — a June wedding in 1931 — was a full-blown church affair, in which he tied the knot with Miss Betty Lyons in southern California. By the time Dudley moved to Alaska, the marriage was over.

After his second divorce, Dudley found himself down on his luck financially. He then landed a road-construction job in Portage, where he met Parsons, who also was working for the Alaska Road Commission.

Parsons liked Dudley personally but called him a “derelict,” recalling that Dudley spent most of his spare time in Portage’s two or three shack-like bars, which were powered by individual light plants and had sprung up to support and to leach the incomes from road workers.

Another of the road men there, Robert Murray, also befriended Dudley at this time. Murray, one of the earliest homesteaders on Longmere Lake, brought Dudley with him to the peninsula in either 1949 or 1950 and allowed him to stay for some time at his place. In fact, Murray thought so much of his friend that he named an east-west road off Murray Lane in Murray Lake Subdivision No. 1 “Dudley Avenue.”

Dudley filed on land of his own — 14 small adjoining parcels near Cook Inlet — in North Kenai in 1955. He also acquired a commercial fishing site just south of the Arness Supply Dock, where he worked as a longshoreman during the 1960s.

It was shortly after his move to North Kenai that Dudley became acquainted with Edith “Eadie” Henderson, the renowned proprietor of the Last Frontier Dine & Dance Club. More commonly referred to simply as “Eadie’s,” the establishment was located near the Wildwood Army Station to attract military clientele as well as Kenai’s large number of fishermen and a burgeoning crowd of oil workers.

<!–

–>

“He was a habitué of Eadie’s just for, uh, ‘sociability,’” recalled Parsons. “He had nothing else to do. That was his second home, and probably in his own environment out there at his homestead he didn’t have much of anything. Probably Dudley went to Eadie’s all the time to either keep warm or to socialize and drink — ’cause he had nothing else in life.”

“Dudley was a good guy,” Parsons added. “He was harmless. He was his own worst enemy, really. And of course, Eadie, she plied him with the booze, and she let him flop out on the floor at night instead of finding his way out north to his homestead. He was always welcome there because Eadie was due the few bucks he had left, you know — and he probably was a handyman there, doing chores and stuff like that, to keep Eadie going and keep the lights on.”

The high living of Dudley’s previous years was gone for good, but the sad end was still a few years off. For George Dudley, the downward spiral had not yet reached its nadir.

TO BE CONTINUED….

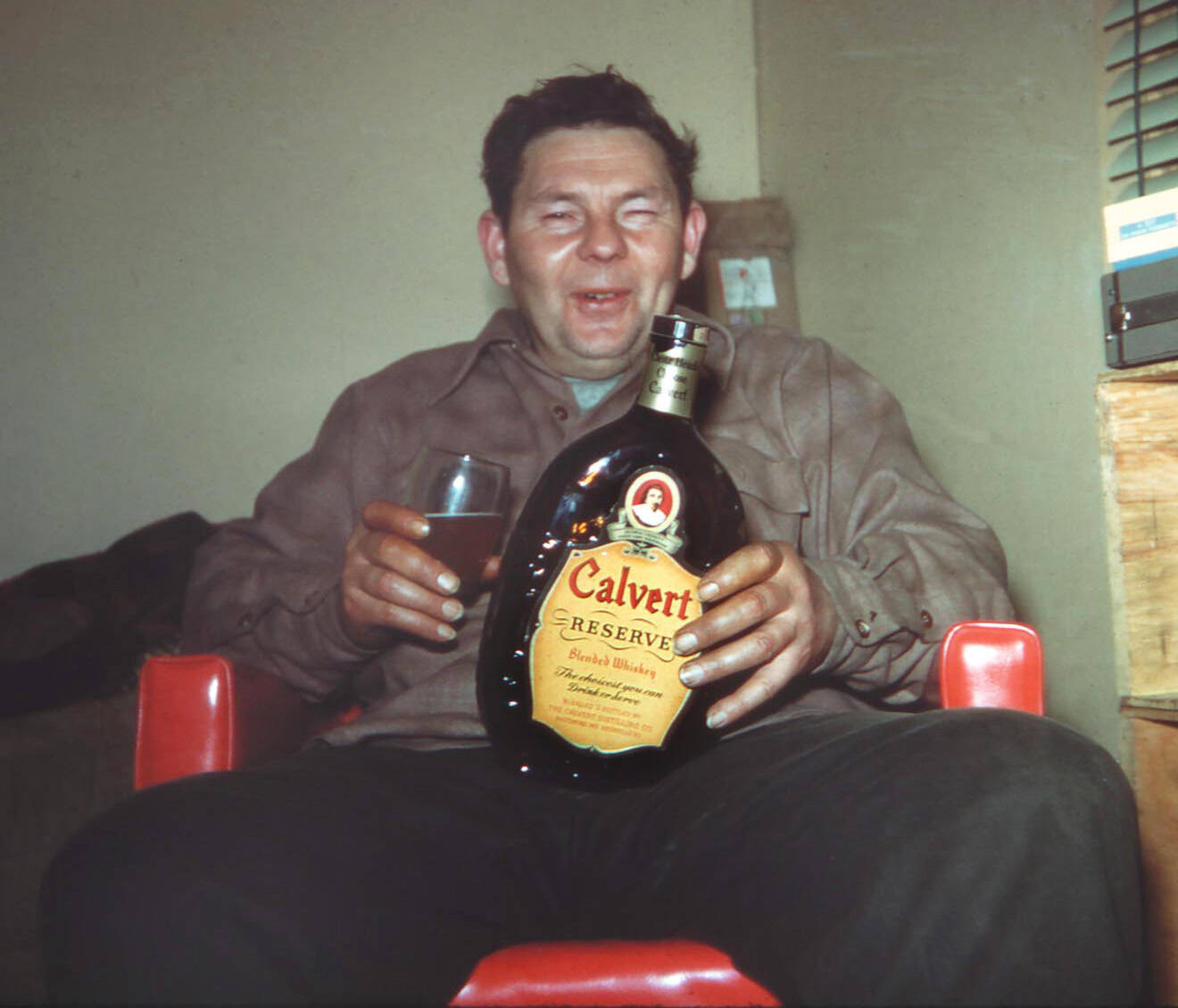

Photo courtesy of Al Hershberger

Former North Kenai resident George Coe Dudley, seen here during the winter of 1950-51, was a hard-drinking man. His messy funeral in 1967 in Kenai echoed his lifestyle.

Former North Kenai resident George Coe Dudley, seen here during the winter of 1950-51, was a hard-drinking man. His messy funeral in 1967 in Kenai echoed his lifestyle. (Photo courtesy of Al Hershberger)

Former North Kenai resident George Coe Dudley, seen here during the winter of 1950-51, was a hard-drinking man. His messy funeral in 1967 in Kenai echoed his lifestyle. (Photo courtesy of Al Hershberger)