‘Cat nights’ are here as Leo, Leo minor, and Lynx constellations prowl the evening sky

United States

Breaking News:

Washington DC

Thursday, May 16, 2024

With the bright moon now out of the evening sky, we are given a chance to observe the felines of the mid-spring sky. We might refer to these as “Cat Nights,” although from an official standpoint April is actually the wrong time of year for them. “Dog Days,” are named for the Dog Star, Sirius, and begin in early July when the weather is hot and sultry.

But then, the cat nights follow, when felines supposedly cry out with yowls that fill the night. Cat nights commence on Aug. 17, and the term stems from an old Irish legend about witches changing themselves into cats.

In our current evening sky, there are several members of the cat family that ride high overhead and toward the south as darkness falls.

Related: Night sky, April 2024: What you can see tonight [maps]

As the winter stars begin to depart in the west this first full month of spring, the ancient Lion — Leo — dominates high in the southern sky at dusk. Leo is among the most ancient of the constellations, with a backward-question mark curve of six stars making the creature’s majestic head and mane of a great westward-facing lion.

Unlike most of the constellations in the zodiac, Leo with its Sickle, really can be pictured as its namesake: A lion in a reclining position, not unlike the Egyptian Sphinx. The Babylonians and other cultures of Southwest Asia associated Leo with the sun, because several thousand years ago the summer solstice occurred when the sun occupied this part of the sky.

The lion most closely associated with this constellation is the Nemean one — the mythological beast which terrorized the Valley of Nemea and was unaffected by ordinary weaponry (such as arrows and spears) due to its impenetrable hide. Killing the Nemean Lion was the first of ten labors that King Eurystheus tasked to Hercules; a job that the king felt was all but impossible to fulfill. Hercules however, succeeded by grasping the lion in his arms and choked it to death.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Blue-white Regulus is the brightest of these at the end of the Sickle’s handle yet the faintest of the 21 stars in the first-magnitude category. Regulus is 79 light years away, and has luminosity 316 times that of our sun. Although it appears singular to the eye, Regulus is actually a quadruple star system composed of four stars that are organized into two pairs. Regulus marks the heart of the lion, but also lies in the handle of the Sickle. When rising and climbing the sky, the Sickle is seen cutting upward.

Algeiba, in the blade of the Sickle, appears as a single star to the naked eye. However, as a telescope of only moderate size will clearly show, it is really one of the most beautiful double stars in the sky. It should really be observed in twilight or moonlight to reveal the contrasting colors — one star appears tinged with a greenish hue; the other a delicate orange-yellow.

Eastward from the Sickle there is a right triangle of stars which also belongs to Leo. At the eastern point of this triangle you will find Denebola, marking the tip of the Lion’s tail.

The Lion is a member of the cat family, but although there are three constellations that represent dogs, there are no cats. Two centuries ago, some star atlases depicted a cat: Felis, the creation of an 18th century Frenchman, Joseph Jerome Le Francais de Lalande (1732-1807). He explained his choice: “I am very fond of cats. I will let this figure scratch on the chart. The starry sky has worried me quite enough in my life, so that now I can have my joke with it.”

Although this celestial feline does not exist today, cat fanciers will be consoled by the fact that along with Leo, there are two other members of the cat family that are well situated and close together in the current evening sky: Leo Minor, the Smaller Lion and Lynx.

As always, our guides for the best telescopes and best binoculars can help you get a closer look at these feline constellations or anything else in the night sky.

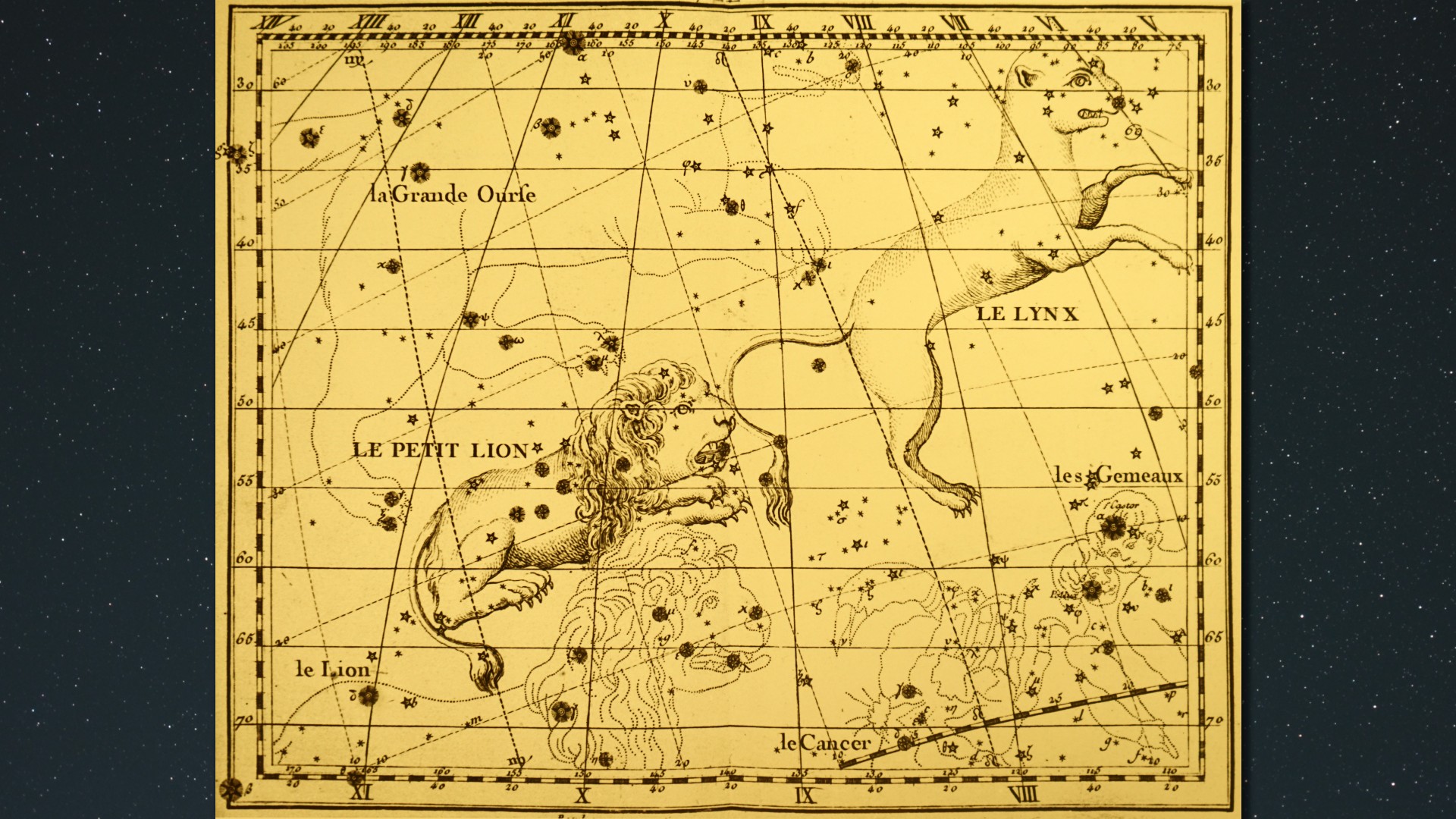

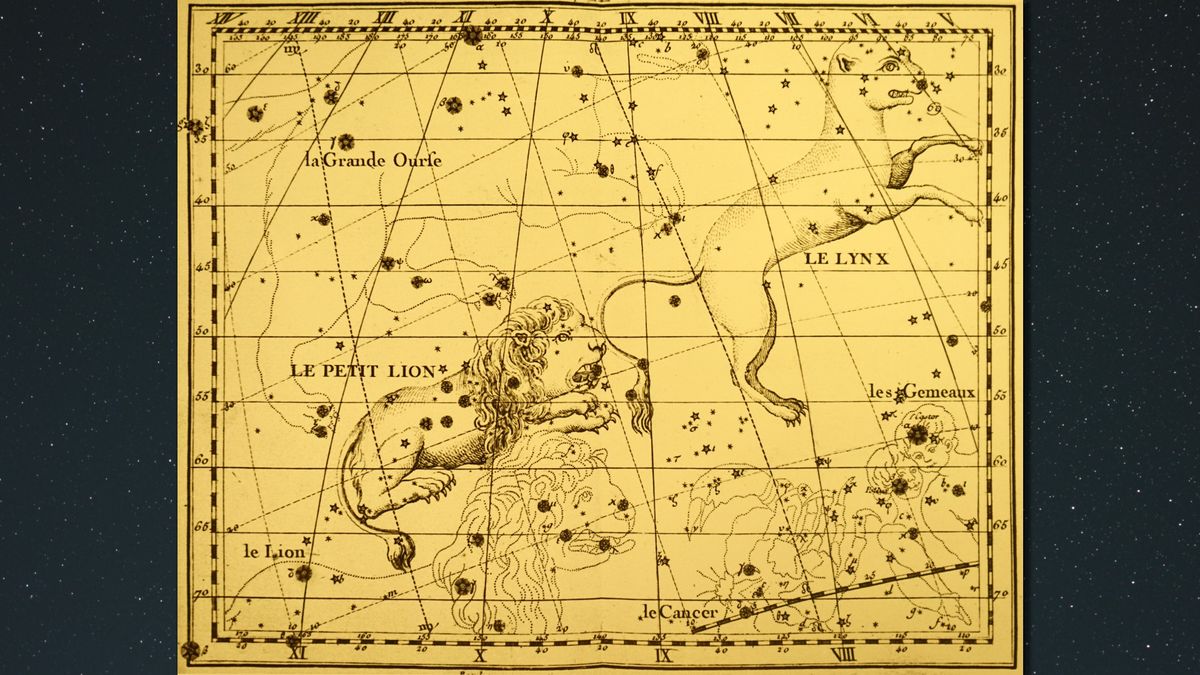

In contrast to Leo, Leo Minor is small and quite faint. recent addition to the constellations, introduced by the Polish astronomer, Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687) a 17th century Renaissance man placed the Smaller Lion in the sky in the year 1687 when he outlined ten new constellations in his star atlas “Firmamentum Sobiescianu.” Besides being an astronomer, Hevelius was an artist, engraver, well-to-do man of affairs and a leading citizen of Danzig, Poland.

Lynx is one of only two animal constellations that has identical Latin and English names (the other is Phoenix, a miraculous bird of great beauty that lived for 500 years). This celestial feline is rather dim and hard to visualize. Like Leo Minor, Lynx was among the ten new constellations created by Hevelius in his 1687-star atlas.

Interestingly, the old astronomy books and star maps, which depicted the constellations as allegorical drawings, placed the lucida (brightest star) of Lynx — orange Alpha Lyncis — in the tuft of its tail. And from these drawings it would seem that nearby Leo Minor, the Smaller Lion, is about to provoke a cat fight by biting Lynx’s tail.

In creating Lynx, Hevelius chose a cat-like animal that possesses excellent eyesight. Ironic, since Lynx itself is a region chiefly devoid of bright stars, and Hevelius openly admitted that “You would have to have a lynx’s eyes to see it!”

To which I’ll close with: That’s simply clawful.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.