Bad Bunny’s Songs of Exile

United States

Breaking News:

Washington DC

Monday, May 6, 2024

Near the end of Bad Bunny’s 2022 World’s Hottest Tour in Las Vegas, all the lights went out. The Puerto Rican singer and rapper filled the darkness before the song “El Apagón” with a six-minute speech in Spanish about what makes his home island bien cabrón—“really fucking awesome.” He highlighted not only Puerto Rico’s beauty but also its resilience in the face of immense challenges: corrupt governance, poor electricity and water access, a hurricane only five years after the devastation of Hurricane María. Although “it is always becoming harder for Puerto Ricans to live on the island,” he said, their strong sense of kinship saves them: “The leaders are the people, who always help one another.”

His speech soon turned into a lament twinged with guilt. “Sometimes I see comments that are like, ‘Where is Bad Bunny?’” he told the stadium. “I’m here, in Las Vegas. This is my job.” The price of fame, he went on to suggest, was a type of exile—work that he cherished but that kept him from the island and people he loved.

Community has long been central to Bad Bunny’s work. The Latin-trap superstar, who has set Spotify streaming records and repeatedly topped the Billboard 200 chart, seldom introduces himself without mentioning where he comes from (accepting the 2022 Video Music Awards Artist of the Year trophy, he declared, “I’m Benito Antonio Martínez, from Puerto Rico to the world!”). He famously resists singing or giving interviews in English. Many of his songs contribute to a long Caribbean musical tradition of rebellion against colonialism. Meanwhile, others form an archive of place; the mountains, rivers, and beaches of Puerto Rico seep into numerous perreo anthems. “This is my beach / This is my sun / This is my land / This is me,” ends the house track “El Apagón,” signaling an understanding of Caribbean people as inextricable from the islands themselves. Bad Bunny’s latest tour and album, however, mark a spiritual departure for the artist, finding him retreating inward to wrestle with cynicism and isolation at the top of the world.

Read: SNL didn’t need subtitles

The ongoing Most Wanted Tour, which began in late February, is less of a communal celebration and more of a solo rodeo. I don’t mean this only metaphorically: Midway through the Barclays Center concert I attended this month in Brooklyn, Bad Bunny appeared onstage atop a real, live horse. In the lead-up to this entrance, the stadium darkened as a three-minute video played on-screen, revealing a desert landscape of desolate sepia tones. “They tell me Jesus was in the desert for 40 days and 40 nights,” the singer growled in Spanish. “I’ve lost count of the years I’ve spent between sand and cactus.” In the video, a masked Bad Bunny, encased in a buckskin jacket, rode a slow-trotting horse into an apocalyptic sunset. “I remain like this,” Bad Bunny said. “Alone.” (At this point, my friend’s 78-year-old Puerto Rican grandmother, whom I attended the concert with, cried out in concern: “We’re here for you, baby!”)

This new lonely-cowboy persona is in line with the artist’s most recent album, Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana, the 22-song trap opera behind this tour. In it, Bad Bunny explores what it means to be the caballo ganadór, or winning horse—at least that’s what he calls himself in the opening track, “Nadie Sabe,” an orchestral rap that samples trampling hooves. In 2022, he was, by several measures, the top artist in the world. Yet he doesn’t seem convinced that the hype is worth the stress. “Everyone wants to be No. 1,” he raps. “If you want it I’ll give it to you, motherfucker.” What fun is being No. 1 when no one can share it with you?

From the get-go, the new tour has approached listeners from a more standoffish posture. “If you’re not a real fan, don’t come,” read the official ads. Instead of energetic house warming up the audience as happened in 2022, this year’s show opened with the longing strings of a classical orchestra. (My friend’s grandmother: “They’re putting me to sleep!”) The ensemble’s rendition of Charles Aznavour’s French ballad “Hier Encore”—which Bad Bunny’s “Monaco” samples—set an early tone for the evening of nostalgia, as if happier days existed largely in the past.

Visually, the Most Wanted Tour was also decidedly placeless, leaning into minimalism and abstraction. At the World’s Hottest Tour show I attended in Las Vegas, the vibe was “beach party”: Bad Bunny appeared in an array of joyful pastels. Dancers in bikinis and denim shorts freestyled under string lights. Visuals showed cartoon dolphins swimming toward island oases. I remember feeling shocked when I left the stadium and stepped into the Mojave Desert’s hot and twisting air. The concert had felt like a portal home to the Dominican Republic, ready to rival JetBlue. I could almost feel the cool shine of the sea melting over my feet.

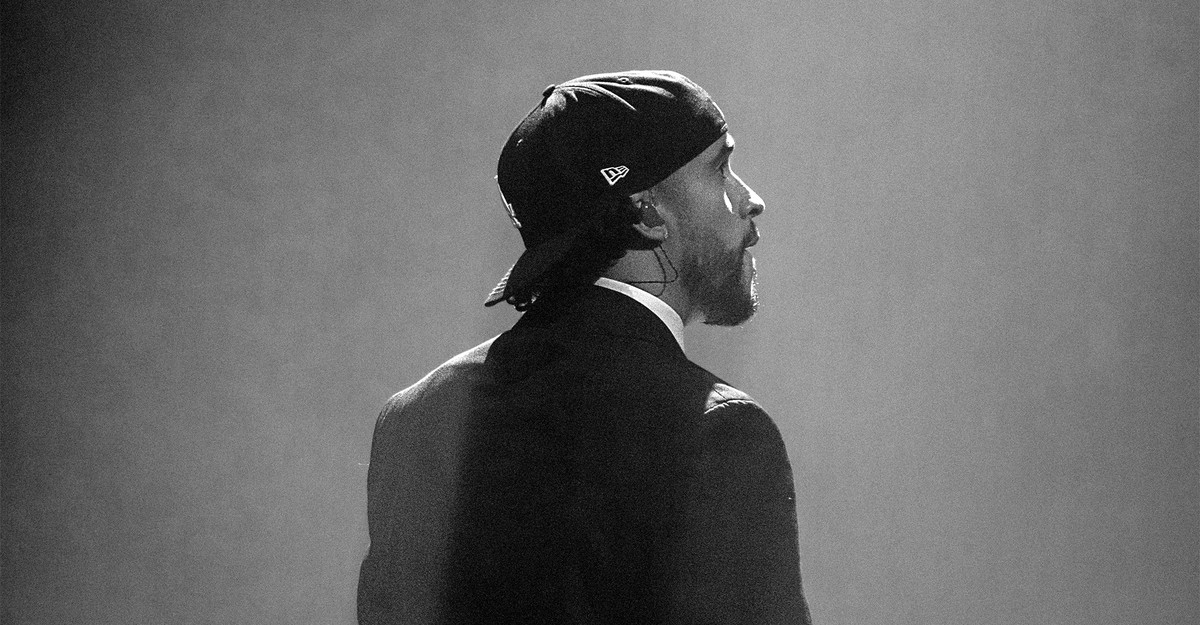

Yet this time around, tropical maximalism was replaced by nondescript, arid visuals and monochrome Yeezy-style fashions. The dancers, dressed in all-black hoodies or chaps, appeared sparingly. Most often, Bad Bunny was onstage by himself, hopping from one end to another while performing trap bops in burgundy cowboy gear.

For much of the performance, he also sported a Spider-Man-style mask or a studded nun’s habit (à la the Virgin Mary)—a tongue-in-cheek choice for a singer frequently criticized for his lewd lyrics. His hidden face added a layer of distance between him and the audience, seemingly signaling how much access to him we should really get to have. Bad Bunny has rebuked the parasocial aspects of fame, including people’s entitlement to his personal space. Throughout the Nadie Sabe album, he makes several references to a much-reported instance in which, during a vacation in the Dominican Republic, he threw a fan’s phone into some bushes after she photographed him without his consent.

Yet despite the lingering specter of celebrity’s dark side, the show’s final act still managed to conjure a wider sense of connection within the audience. Bad Bunny ended with a slew of his reggaeton hits, old and new, and segued into his song “Tití Me Preguntó” with a roll call of places—asking where, among other groups, his Ecuadorians, Mexicans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans were at. With each mention, the stadium erupted into ecstatic screams of recognition. Flags rippled; decibels flared. The rare roar of a crowd of Dominicans, all in one place in the U.S., immediately brought tears to my eyes. Once the song started, we screamed back his lyrics about bringing a roster of girlfriends to his VIP table. We in the audience were there, together. Meanwhile, Bad Bunny looped the stage, alone again.